SmartBear's 2020 API report finds 'Accurate and detailed documentation' to be second-most important characteristic of APIs

- Report overview

- What’s broken

- Two ways documentation processes are broken

- Possible quality control mechanisms for docs

- Conclusion

- Your feedback

Report overview

You can download the SmartBear report here: 2020 The State of API report (some information fields are required before you can download the PDF). The report is short, but if you’re pressed for time, just read “API Strategies” (pgs 10-18) and “API Documentation” (pgs 42-47).

Here are the highlights that will make technical writers puff up their chests with pride:

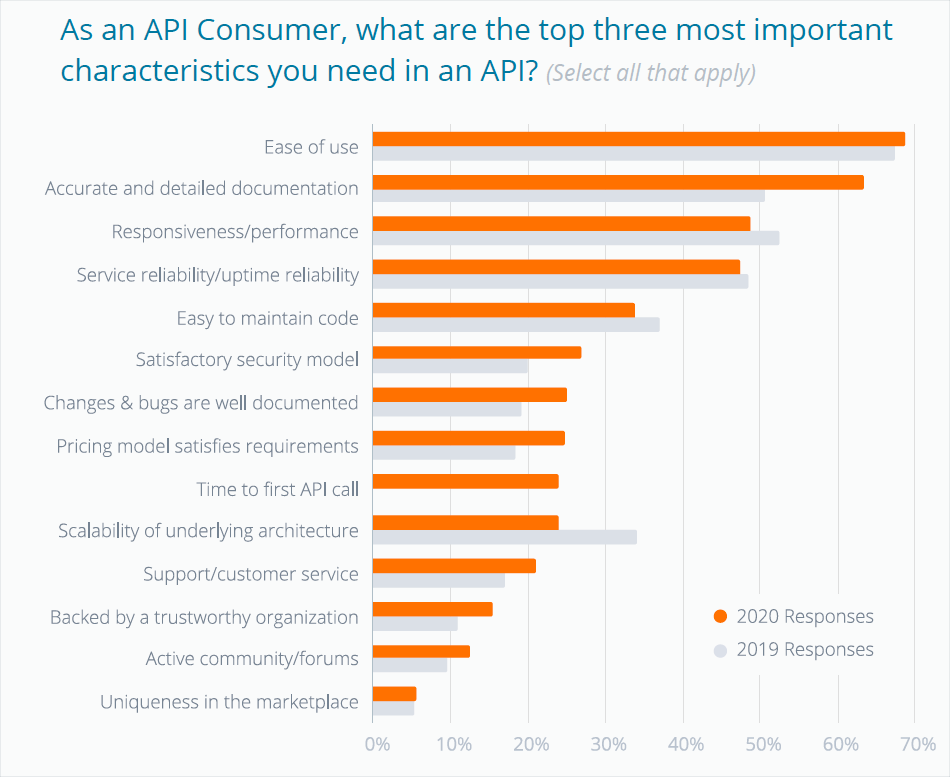

While the top 3 most important characteristics in an API remained the same year over year, Accurate and detailed documentation beat out Responsiveness/ performance for the 2nd position with a significant 13% increase. For context, when we asked the same question in 2016, only 25% of respondents selected documentation as a top factor. This year, 63% of respondents chose it.

Not only did documentation remain high on the list of important characteristics — it actually shot up 13% from last year.

I almost feel like including this screenshot in my email signature, or making T-shirts with the graphic. The report follows up this graphic with an astute observation that rankings depend on the group doing the ranking: API producers identify different important characteristics than API consumers:

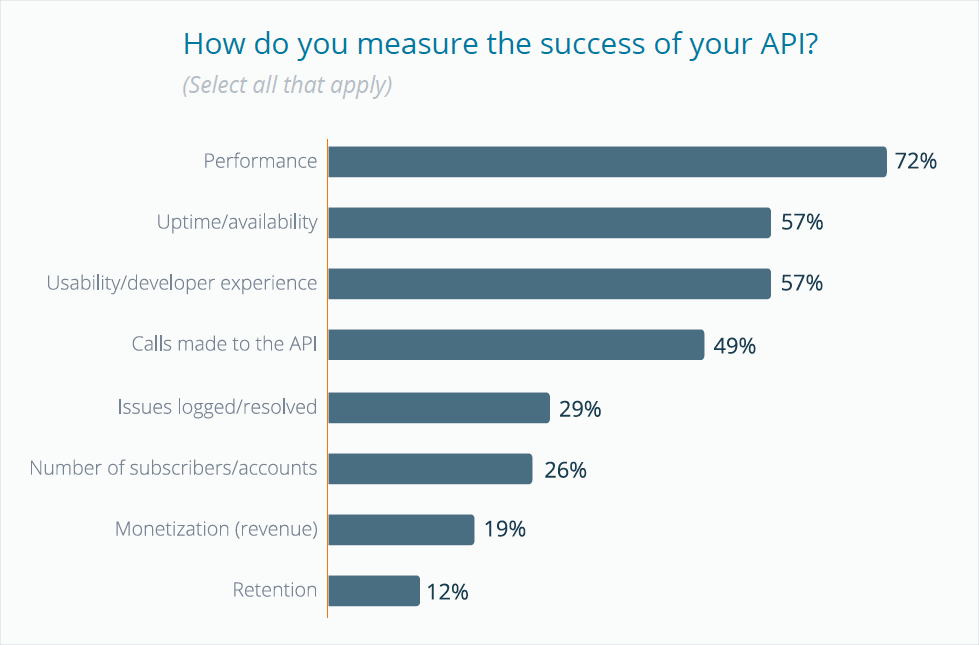

While Performance rates number one overall for API success [for API producers], to the API consumer Ease of Use and Accurate Documentation are the top choices.

In other words, for developers consuming the API (API consumers), ease of use and accurate docs are the most important, whereas for internal dev teams (API producers), performance and uptime/availability are the most important characteristics. Here’s what matters to internal teams producing APIs:

The juxtaposition of these two graphics say a lot. Why is there misalignment between what’s important for API producers and what’s important for API consumers? Wasn’t the whole point of agile development to help align what dev teams create with what’s important for the audience?

In my experience, documentation hardly gets the attention it should merit (based on API consumer rankings here). For example, how many product engineering meetings have you been in that focused on ease of use and accurate and detailed documentation rather than performance and uptime/availability? Most meetings focus heavily on technical matters and very few meetings (maybe less than 10%) focus on ease of use (the developer experience) and accurate and detailed documentation.

Perhaps many API consumers take these characteristics for granted, assuming that performance and uptime/availability will be in place while in fact dev teams struggle to figure them out. But if API consumers esteem documentation to be so important, why don’t dev teams prioritize it more? The report says that basically, teams don’t have the time or resources for docs:

According to 64% of the survey participants, Limited time is the biggest obstacle to providing up-to-date API documentation. Following that, 47% of the organizations surveyed deal with API Documentation that is now out of sync with the API implementation. Lastly, for 29% of respondents, they could deal with the problem of outdated API documentation if they had more personnel.

Admittedly, if we’re expecting engineers to write docs while simultaneously writing code, it’s no wonder they lack the time, or that they do it in haste and without the care and meticulousness the activity requires (trying to cram in the docs alongside other extensive coding tickets).

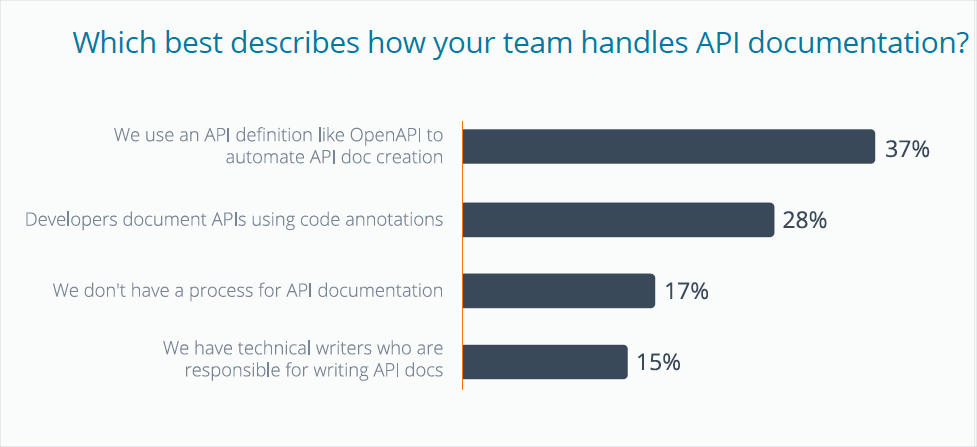

In some places, the SmartBear report seems to suggest that generating docs from an OpenAPI spec is the main request/process around docs, and that most engineering teams can handle this documentation task without technical writers. They only mention technical writers as a fallback to engineers who can’t auto-generate API docs from the spec:

Without the option to render machine-readable code, 15% of the organizations use technical writers to create API documentation.

Here’s the accompanying graphic:

This mention of tech writers always catches me by surprise here. To me, it feels like it portrays tech writers as an antiquated group of crafts-people who are writing documentation laboriously by hand with pencils. In my survey on dev doc trends, most API docs (including reference) are generated as a collaborative effort between tech writers and engineers.

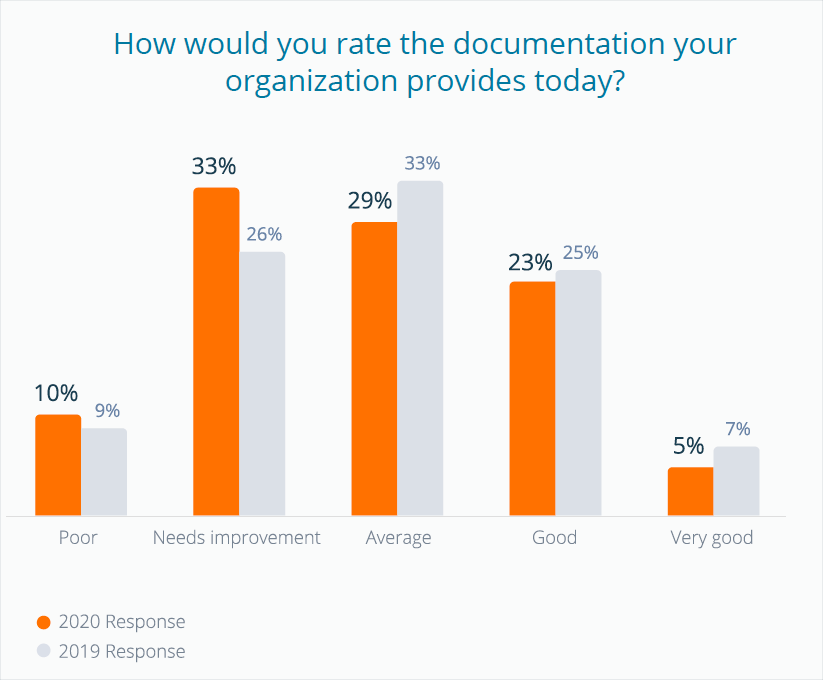

The SmartBear report also finds that most survey respondents feel their docs are sub-par and in need of improvement:

Documentation is so important to the successful adoption of an API, and yet 43% of survey participants indicated their documentation was poor and needs improvement. Most organizations (52%) rated their API documentation Good to Average. Only 5% of the survey respondents felt their API documentation was Very good.

I’m curious whether developers would answer the question similarly about their APIs or other code (rating them as poor). Whatever the reason, most people feel that docs need a lot of improvement. Documentation is one of those categories of products that, if it were rated on Amazon, all products in the category would rarely climb above three stars — very good docs are rare.

Reading this part of the report, about how most people think their docs are below average, I started to wonder if something is broken with documentation processes in the software industry. I mean, if the result is below average, what is contributing to that result? Is the process that produces the result flawed in some way? More on this later.

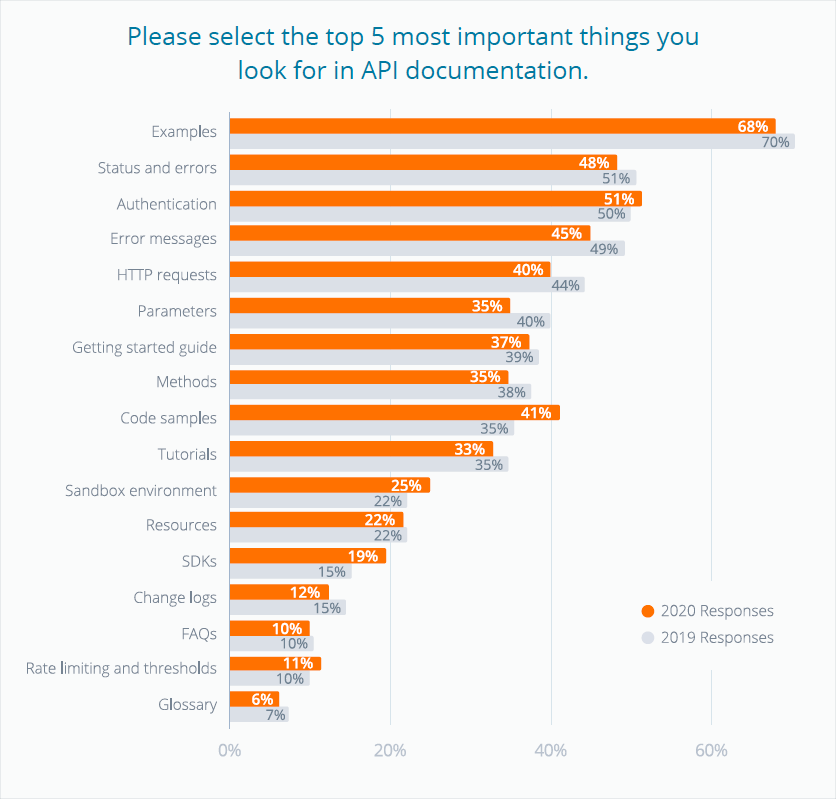

The SmartBear report asks respondents which docs have the highest priority based on user needs. It turns out that “examples” top the list by a wide margin:

Of all the elements that make up successful API documentation, the desire for Examples is the top choice for the second year in a row, coming in at 70%. A close tie for the next three spots is Status and errors at 51%, Authentications at 50%, and Error messages at 49% of survey respondents.

I admit that I’m a little confused at how “examples” differ from “code samples,” and the report never explains what examples are. I assume examples refer to sample apps, for the most part, or more extensive, holistic code. Not just a small code snippet but an actual working example of an implemented API.

Regardless of the lack of clarity about examples, the previous screenshot is golden for the way it highlights different components of API tech docs. In fact, I’m inclined to print out a list like this as a quality checklist for docs. In looking at the list, the report authors make another interesting observation:

From the exhaustive list of items and active responses across categories one begins to understand … the scope of work required to create and maintain documentation.

Amen to that! Yes, when you start thinking about all the topics and components required for good documentation — not only examples (sample apps?), but documentation about error messages, getting started guides, tutorials, changelogs, glossaries, and on and on — the scope and effort required to produce “very good” docs feels daunting.

What’s broken

While the report does an excellent job of highlighting the importance of docs, the report also suggests that documentation has many challenges and opportunities. To recap some of these findings that underscore the need for improvement:

- Docs rank as the second-most important characteristic of an API, but software teams rarely reflect this importance in their API development processes.

- Only 23% of teams consider their documentation to be “good,” and only 5% consider is “very good.”

- 64% say limited time is the biggest obstacle to providing updated API docs.

- 47% say their docs are out of sync with the API implementation.

While I’m floored to see the importance of documentation highlighted in such a prominent way, I’m skeptical that the report will change the industry. Do we expect that product and engineering teams all over the country will start reading this report and think, hey, maybe it’s time for us to allocate headcount for a dedicated technical writer on our team! In other words, is this report going to affect the software industry in a way that fixes documentation? Unfortunately, I doubt it.

But my larger question is how documentation got into such a beat-up state in the first place? Poorly resourced, never enough time for it, out of date, below average in quality — despite customers saying it’s the second most important factor in APIs. What happened here? Are the processes that development teams use to create documentation in need of restructuring? Do we need to approach documentation in a different way than we’re currently doing? How do we raise the quality of documentation from “below average” to “very good”?

Two ways documentation processes are broken

There are at least two reasons why documentation processes have “big opportunities for improvement” with software development teams. In other words, there are a couple of reasons why the process for creating docs is somewhat broken within the software industry.

1. Scrum marginalizes docs

We can thank the authors of Scrum for de-emphasizing the importance of documentation by proclaiming “Working software over comprehensive documentation” in the Manifesto for Agile Software Development. Even if the intent wasn’t meant to include end-user documentation, the Scrum authors never clarified this (as far as I know) nor do they include documentation as part of the sprint development process. For example, during sprint demos, features are demo’d. Where do docs fit into the demo process? What is their cadence? Who reviews docs and when? None of this is mentioned or considered in Scrum development methodologies, which tend to be the default process that software teams follow.

Tech writers have never fit neatly into the Scrum model, where engineers are fully dedicated but tech writers are spread thin across half a dozen projects and treated in ad hoc ways (e.g., docs are rarely assigned points or reflected in burn-down charts). (For more on this topic, see Tech docs and Agile: Problems with integrating tech writers into engineering Scrums (Part 1).)

2. No built-in quality control mechanism

A more formalized recognition of documentation and a more integral role in Scrum would be helpful, but there’s a larger issue with roles and responsibilities that’s missing. Dev has QA to quality-check the code devs write, but who quality-checks the docs that tech writers create? Tech writers can pretty much write what they want, get an overworked/hurried engineer to nod approval, and then hit publish (processes vary by organization, of course). There’s rarely a stringent quality control mechanism enforced with docs like there is with code, and as a result, documentation can fail to meet the quality standards that organizations want to achieve.

To illustrate, what developer shop would feel comfortable implementing a software development process that doesn’t involve QA? But for writers, who QAs the documentation? Devs (the same ones who create the product and who are overworked as is with too many development tasks) are often the QA. To better understand why devs might not have the bandwidth to review docs, see this video: Why Do So Many Programmers Lose Hope?.

Developers would rarely push code straight to production without getting approval from the QA team. Granted, some developers fill hybrid-QA roles, so it’s not this black and white. But there’s a strong tradition of QA acting as quality control for devs, but no tradition of any role acting as a stringent quality control mechanism for writers.

Note that when I say “mechanism,” I’m referring to some more integral checkpoint built into a process — something that writers can’t easily bypass and ignore when it’s inconvenient to follow it. In the next section, I’ll review some common practices writers follow for documentation quality.

Possible quality control mechanisms for docs

The following are possible quality control mechanisms for docs.

Editors

Let’s start with the most traditional way doc quality is encouraged: an editor. For example, a journal has an editorial review board that ensures the articles they publish meet a quality standard. Don’t docs work the same way?

Yes, some doc teams have editors that review docs and ensure they meet a quality bar. However, these editors tend to focus mostly on style more than accuracy or completeness of content. Usually, editors don’t have the bandwidth or expertise to step through the instructions themselves as a test user to assess the content, which is the most important feedback to collect.

Editors do perform an important role (and I’m not trying to minimize that), but while editors can make sure that, for example, reference docs follow the right pattern and terminology, they rarely would assess whether the workflow for using the reference is correct.

QA team

One approach might be to have an editor review docs for style, and have the QA team review docs for accuracy. This could create a more holistic check from different perspectives.

Yes, QA members can review docs for accuracy, but few QA teams ever feel it’s their responsibility to review docs, and like developers, they lack bandwidth. Also, in my experience, the doc reviews from QA tend to be trivial and don’t assess clarity (such as whether a user could understand and follow the instructions). QA can still play a valuable role, though, and maybe this is a channel I haven’t pursued enough. Perhaps with some training, QA could deliver better doc reviews.

Usability testing

Another approach could be to test docs with actual users. Writers could bring in users for beta testing of docs, or use other tech employees as user proxies. Then writers could observe users in a usability lab as the users proceeded through the instructions. (I once did that here: A Few Notes from Usability Testing: Video Tutorials Get Watched, Text Gets Skipped.)

This is certainly the gold standard for quality control. However, deadlines rarely accommodate usability testing like this, nor could it be done on a regular basis with each iteration of docs. Additionally, especially with API docs, it’s often not possible to do quick user tests. Many of the products I work on take at least a week to implement, if not multiple weeks. It would also be challenging to select a representative sample of users with different technical backgrounds and product familiarity. It might be misleading to draw a conclusion based on five test users who don’t properly reflect the actual users.

Formal signoffs

Some teams implement required formal signoffs before publishing docs. These mechanisms are often implemented after a product manager becomes upset about something that was incorrectly published in docs and so implements tighter preventative controls.

The problem with stricter signoff controls is that not all changes merit formal signoff. Imagine following the same release process for fixing a typo as for the first release of new software. Also, if you have to get 100 approvals to publish anything, this creates a bottleneck to being able to publish in a more rapid, dynamic way that fits the pace of agile development. If you release on a weekly basis, and you have to gather ten signatures for each release, this seems like a bureaucratic nightmare, especially if some approvers are slow to respond to email.

Multi-stage doc review

My current process for quality control (and I’m not saying it’s the best) is to implement an informal five-step review process that involves the following:

- Review with doc team (me — I have to be able to make the instructions work for myself)

- Review with product team (the ones who created the software have to approve the docs)

- Review with field engineers and support teams (our field engineers interface with partners and represent the voice of the developer, so I try to get their review and approval)

- Review with Legal (if I think it’s warranted, I’ll run it by Legal)

- Review with beta users (if the product has a beta, I monitor feedback from beta users — this feedback usually comes back through field engineers and PMs)

I try to push docs through these stages of review and get an informal approval from each group. I use my best judgment to modify the stages based on the edits. For small changes involving style or organization, I might bypass all stages of review and just publish the updates directly. For any changes to content, though, I touch base with the relevant groups to review the updates.

Although I’ve described this five-step review process to teams, the timelines I work in don’t always accommodate all levels of review. I’m working on a documentation project now that’s a good example. The product team literally gave me two weeks to work on documentation for something they spent a year developing. I think a more reasonable timeline would have been 1-2 months. Partly it’s my fault for not providing clear requirements around timelines and review processes ahead of time to the teams, especially when I saw the product on the roadmap horizon long before.

Development has a multi-stage process as well. Code often has a pre-development stage where conceptually the ideas are floated to partners to assess interest. If green-lighted, the product team codes a minimum viable product and shares it with beta users. After some more feedback and iterations on the product, eventually the product is released more generally. As long as docs stays in step with these stages, then we benefit from the multi-stage review as well. The challenge is that writing in tandem with agile development means a lot of re-writing and churn, expanding the scope of any project to two or three times the effort.

Regulatory standards

Other industries often have regulatory standards that docs must meet. (In fact, someone once asked if I would participate in creating a regulatory standard for API docs, though I passed on this because no company I’ve ever worked with has used regulatory standards.) Standards are more common in Europe and industries outside of software. For example, the airline industry and the pharmaceutical industry have standards for documentation. The standards aren’t just best practices but hard requirements for the product to launch. With a standard, regulatory bodies would provide the quality control mechanism for docs. (For a good example of pharma requirements, listen to this podcast from Larry Swanson: Scott Abel: The Content Wrangler – Episode 081.)

I like the idea of a standard, but who would enforce it in industries where it’s not required? Would tech writers have to champion the adoption and integration of the standard within the organization? How specific would the standard be? For example, would the standard require a specific sentence reading level? Would it require all error messages to be defined in the documentation? I can see how some best practices might not always apply.

Working sample apps

Another approach for quality control is to complement documentation with a sample app. The sample app does a tremendous job of ensuring that the steps in the documentation achieve the advertised result. If you can walk through each of your documentation steps in a sample app, and you get the right result (e.g., the sample app does what it’s supposed to), there’s a good chance that the docs will be accurate. Even if the docs miss some detail, users can always infer the right configuration by looking at the sample app.

Not all projects have sample apps, and this is definitely one area where norms in one industry differ from other industry norms. But championing sample apps as a quality control check has the additional advantage of providing “Examples” to users, which is their most requested type of documentation per the SmartBear survey.

Reduced project allocations

Another quality control mechanism could be to reduce the number of projects you’re allocated to. I described this approach in two recent posts:

- Part IV: Engaging deep enough to blur the lines between content and product design

- Playing a product design role as a content designer – podcast with Jonathon Colman

The idea is that writers who engaged on 1-2 projects only can likely have the bandwidth necessary to create great docs, as well as play quasi-product-design roles. When one starts to examine what’s required for “very good” docs (the long list shown earlier in the SmartBear summary), people start to realize the required resourcing (“the scope of work required”) to write docs. And when you develop deep-level expertise, you can apply that to more than just documentation — you can influence the product design and roadmap.

That said, I doubt that many of us could radically pivot towards this 1-2 projects only model. It would require organizational buy-in and resourcing.

Definition of done

Another approach for quality is to change the “definition of done” with tickets. If a ticket has doc impact, it can’t be marked as resolved or closed until the impacting documentation task has also been completed. Implementing this requires buy-in from the software development team and also some decisions about how to close tickets for sprints when the docs are incomplete.

Developers are often keen to close tickets at the end of a sprint because it shows that their work has been completed. Writers might not always be able to keep up with each ticket closed, especially if the ticket is closed on the last day of the sprint. It’s probably not too difficult to find a workaround here, but you need to have the software development manager (or Scrummaster) on board with the definition of done.

Conclusion

Overall, what is the best quality control for docs? In what ways can this quality control be enforced, so that it can’t be overlooked or ignored? A good mechanism is one that requires you to follow it because it’s baked into the process or tools themselves. For example, if your intake process populates a ticket with a list of required fields, it enforces information collection into the process itself rather than being a best practice to remember.

When I look over the list of possible quality controls, from those I’ve tried, what works best for me are sample apps and multistage doc reviews. Changing the “definition of done” also helps. However, I’d like to gather your feedback and insights about this topic. I still feel like we need a better forcing function for quality control with docs.

Your feedback

Please take this short survey to provide your input. You can view the ongoing responses here.

About Tom Johnson

I'm an API technical writer based in the Seattle area. On this blog, I write about topics related to technical writing and communication — such as software documentation, API documentation, AI, information architecture, content strategy, writing processes, plain language, tech comm careers, and more. Check out my API documentation course if you're looking for more info about documenting APIs. Or see my posts on AI and AI course section for more on the latest in AI and tech comm.

If you're a technical writer and want to keep on top of the latest trends in the tech comm, be sure to subscribe to email updates below. You can also learn more about me or contact me. Finally, note that the opinions I express on my blog are my own points of view, not that of my employer.